Parachuted in to turn around a failing giant of the British high street, Robert McDonald was part of Woolworths’s last roll of the dice.

The new finance director said he was excited to join an “iconic” brand when he began work in early November 2008, but just three weeks later the company would sink into administration.

And there was little the company’s last ever executive hire could do to stop the famous store – known for its pick ‘n’ mix, homeware and everything in between – from closing for good on 6 January 2009.

“Like everyone my age, I had grown up thinking its existence was a normal part of life,” Mr McDonald told Sky News.

“I was very pleased to have the opportunity to work there. I knew it was going through hard times and looked forward to being able to help.

“But, sadly, it was past that by the time I joined, and the end seemed very swift.”

Analysts blame its downfall on a toxic combination of low cash reserves, lost credit insurance and crippling debt – all exacerbated by the 2008 financial crisis.

It marked the end of Woolies’s near century-long presence on the high street, with more than 800 stores closed down and about 27,000 jobs lost.

For many of its staff, news of Woolworths’s demise into administration came from the media, with earlier rumours confirmed in reports on 26 November 2008.

Paul Seaton, who had worked as a store manager and as part of the IT team during 25 years at the company, said his colleagues “crowded around the TV” to hear their worst fears confirmed.

“It just all fell to pieces after that,” Mr Seaton, now 61, told Sky News.

“The sad reality is Woolworths took 99 years to build, and it took 42 days from administration to the day the last door shut. 99 years of meticulous care and thought… gone.”

The board insisted administration wouldn’t detract from “business as usual”, Mr Seaton said, but that all changed when he was called to a meeting on 5 December.

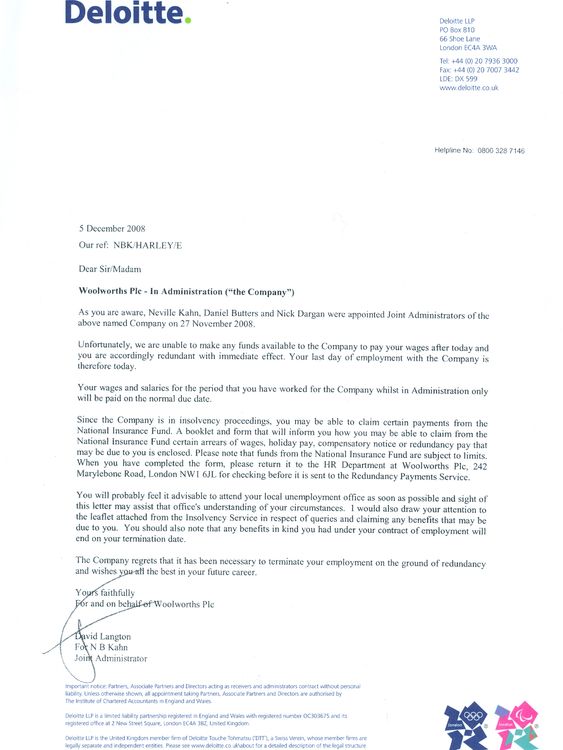

He was among 500 senior figures gathered at Woolworths HQ, where each was given a letter written by administrators Deloitte notifying none would be paid another day and all had lost their jobs with immediate effect.

“We were summoned and told not to come back, all 500 of us,” Mr Seaton said, adding their passes into the building were deactivated on the spot. “The business only carried on for one month after that.”

While his time at the company came to an abrupt end, he dedicated time to creating a virtual Woolworths museum, preserving memorabilia and documenting the chain’s long history.

A store for the family

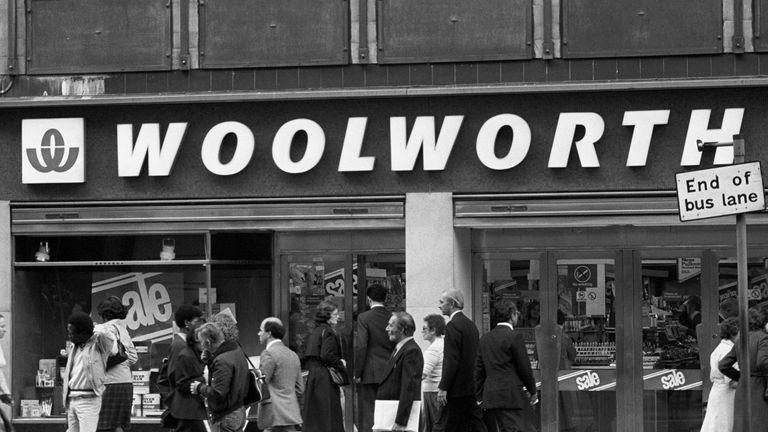

The first store opened in November 1909 in Liverpool, by New Yorker Frank Woolworth, who had already established the brand in the US.

In a prescient diary entry, he wrote during an earlier trip to Europe that “a good penny and sixpence store, run by a live Yankee, would be a sensation here”.

Such was the success of the UK counterpart, his successor Byron Miller reportedly beamed that “the child has long since outgrown the parent”.

Mr Seaton thinks the literal child-parent relationship was key to the store’s popularity.

“There used to be old adage that people need Tesco because everyone has to eat, and people trust Boots because you call the manager ‘doctor’, but they went to Woolworths because they love Woolworths,” he said.

“Have you ever heard a kid saying ‘mum I want to go to Tesco’? The whole reason I loved being a manager is kids and families loved coming to Woolworths.”

The store’s name lives on in Australia – though has no connection with US or UK equivalents – where it is the country’s largest supermarket chain and last year recorded a net profit of $1.62bn (about £87bn).

US stores closed in 1997, but the UK branches recorded a record profit topping £100m just one year later.

What went wrong?

Customers were still shopping at the UK stores, and in the firm’s final annual report the company made a slight pre-tax profit in 2007.

But even with some signs of recovery ahead of 2008, Woolworths had a terminal problem: modest cash flow and a £385m mountain of debt.

Retail expert Clare Bailey was among the consultants drafted in 2006 to tackle the mammoth task of detangling the company’s supply chain, which she says was collecting too much of some stock and too little of others.

As banks began to lose faith in Woolworths’s finances, the firm had its credit insurance withdrawn – meaning it had to pay suppliers immediately, rather than in instalments.

To make matters worse, many Woolworths stores were sold a few years before and rented back at a price that only appeared to increase over the years.

Left with fewer assets, little in way of cash reserves and no credit insurance, the retailer was not prepared for the coming shock of the 2008 financial crisis.

“Cashflow is like oxygen,” Ms Bailey told Sky News. “You can be profitable, but if you haven’t got cash to pay bills or for when something goes wrong, then that’s it – game over.”

The company reported a pre-tax loss of £90.8m over the first half of 2008 in September that year, despite launching the WorthIt range – promoting low-cost products – in 2007.

Losing sales and customers

One of the big issues Ms Bailey identified in the supply chain was a failure to keep evergreen products on shelves.

For example, she said only 20 stores out of more than 800 nationwide had the correct amount of coat hangers, a product that sells all year, while others bought far too many Christmas trees.

It meant money was “trapped in stocks”, she said, and would gradually turn customers away.

“And if you replicate that through other products, customers could find what they didn’t want, but not what they wanted,” she said.

“You might, as a customer, give them the benefit of the doubt a few times, but eventually they will turn to other places. So, they not only lost the sale – they also lost the customers.”

It’s this perceived neglect of the customer journey that small business growth expert Claire Hancott believes cost Woolworths at the turn of the century.

Footfall almost halved from 7.5 million in 2000 to around 4.5 million in 2007, she said, while the market for Woolworths’s once-popular CDs was shrinking as more consumers headed to the internet.

“Businesses can’t ignore these big trends, even if they won’t come into play for years,” Ms Hancott told Sky News.

“Blockbusters was a classic example, when they thought digital films wouldn’t take off.

“Woolworths wasn’t at the forefront of consumer technology and it’s so important to be looking 10, 20 years into the future – it takes a long time to prepare.”

Discount stores such as pound shops began to pop up on the high street, adding to growing competition that ultimately forced an attempt to sell the company in November 2008 for – ironically – just £1.

It was hoped a sale to restructuring experts Hilco would give them the job of repaying the debt, but the banks rejected the move.

The company went into administration just days later.

A false dawn, but will the sun rise on Woolworths again?

Ever since the company collapsed under the weight of its debt, rumours of a potential return to the high street have never been completely quashed.

A fake announcement – made by a social media account falsely claiming to be run by Woolworths – heralding a comeback was met with excitement in 2020, with savings platform Raisin UK reporting 44% of people discussing the store’s revival online “loved the news”.

In August 2022, pollsters at YouGov found 49% of survey respondents said they wished they could bring back Woolies – a far higher proportion than any other defunct chain.

But for all the hopes of an encore, some of those involved with the firm rue the time that has since been lost – and believe it may have even survived.

“I came in at the end of 2006, but the work we were doing can take three or five years,” Ms Bailey said. “Maybe they started too late.”

All but a small handful of the Woolworths stores were re-let to other retailers within a decade, she added, meaning the spaces “still had merit in the local community”.

“The inner workings of a business are quite complicated,” she said.

“But I think it’s a sad situation it collapsed, because – had they been given a stay of execution – they may well have been successful in turning it around.”

Read more:

Christmas tree from 1920s Woolworths sells for ‘astonishing’ price

Next raises profit forecast but warns stock could be delayed by Red Sea attacks

Ms Hancott agrees: “In another time, would it have crumbled? That’s the million-pound question that nobody will be able to answer.

“Had it not been in the midst of a crisis, then it may have survived.”

For Mr McDonald, a chance to draw on his experience handling company finances never materialised.

It was, nonetheless, a “fascinating experience”, he said.

“It’s such a shame we didn’t have longer to turn that business around,” he said.

“I joined as part of a turnaround plan, but it was too late to change the course of history.”