“When the time comes, disconnect the main flex cable.”

Besides being a short guy named Tom, I never felt I had any sort of Mission: Impossible credentials until I donned safety googles and got handed a screwdriver and plastic scalpel at what’s thought to be the UK’s biggest phone recycling factory.

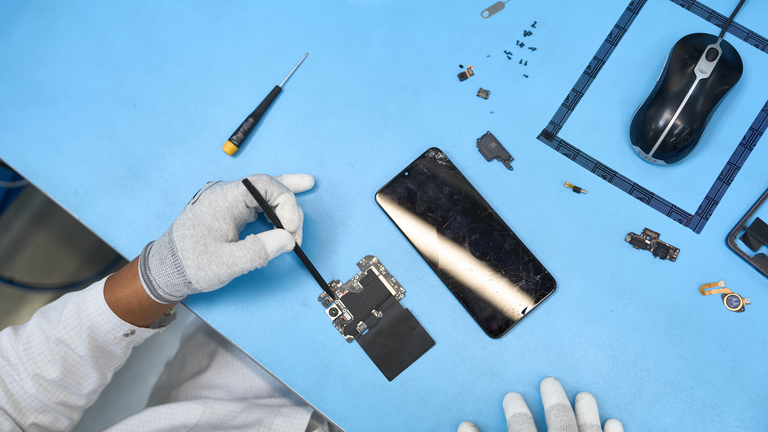

Fixing the screen on a Samsung handset isn’t quite cutting wires on a nuclear bomb, admittedly, but for someone whose DIY experience doesn’t go far beyond putting toppled Lego back together, it was quite the thrill.

Having already used a screwdriver no fewer than 18 times to get into the device’s complex interior components, the next step was removing that aforementioned flex cable.

These are what connect up some of the phone’s most important features, like the touchscreen, to the motherboard – and this phone needed a new one.

It was a relatively basic task, though not one I was trusted with enough to perform on a real customer’s device.

In the time it took me to remove those screws, the technician sat in front of me had likely fixed a few of the more than 900 devices processed at the Ingram Micro Lifecycle hub in Norwich each day.

The 34-year-old facility, with a floor big enough to hold 20 tennis courts, has around 800 employees.

Many are highly-trained technicians, deployed at stations with dedicated equipment for everything from realigning a phone’s broken camera system to replacing those all-important flex cables.

Facility ‘purpose built’ to recycle phones

Kevin Coleman, the facility’s fourth employee back in 1989 and now one of its most senior leaders, says there are “hundreds of technical functions” going on at all times.

“The facility is purpose built to industrialise high-volume processing of tech devices,” he says.

“Predominantly mobile, but also wearables, tablets, earbuds, and laptops.”

I even spotted a Nintendo Switch games console at one station – and it wasn’t for staff to sneak in a cheeky race on Mario Kart between jobs.

Of course, phones are the focus – and the range of those alone is quite extraordinary.

There are shelves and trolleys stacked with iPhones, Samsung Galaxies and Google Pixels of all colours and sizes; damaged or broken in their own way; with every technician trained to handle whichever one might come to them.

Old phones ‘should never go to landfill’

They end up with Ingram’s workers via Virgin Media O2‘s recycle scheme, which lets people, regardless of network, submit their phone for repair or recycling.

Last year, it paid out £36m to people who sold their phones – and plenty are choosing to buy second-hand.

Gina Mutonono, who works on the network’s sustainability initiatives, said the cost of living crisis was one of the reasons there was a “growing acceptance from customers for refurbished devices”.

It helps that many of the phones that go through the facility come out looking good as new – and if they’re too old or just not sellable, there are likely still useful parts within.

“Consumers who are sending us smashed phones don’t always realise even if we cannot sell them, that they’re still worth something,” says Mutonono.

“We can always reuse some parts, like metals or batteries – they should never go to landfill.”

The huge number of phones going to waste

Five billion phones are estimated to have been thrown away worldwide last year, but less than 20% of e-waste is recycled and ends up part of Mutonono’s cherished “circular economy”.

There are also thought to be tens of millions of unused electronics sitting in Britons’ drawers and cupboards.

A study last year revealed the estimated worth of spare smartphones alone was £1bn.

To make the most of everything that ends up at the Norwich facility, new recruits go through its classroom-like training centre. Given the nature of the tech world, veterans need to return regularly as new handsets are released.

They’re taught how to disassemble phones and put them back together, just as I got to try – albeit with the help of a Jedi-like engineering sage at my side and a detailed set of instructions.

Hot wires and phone freezers

Resembling some kind of futuristic city for Borrowers, these phones might be small, but the interiors are packed with quite incredible amounts of component parts.

The screen alone is made up of a display module inside the device, the LCD or OLED panel, and a sheet of glass you likely tap and swipe hundreds or thousands of times a day. The degree of damage, whether it’s minor scratches or a complete smash, determines just how multistaged a screen repair job might be.

I watched on completely transfixed as a woman removed the pane of glass from a display using a hot wire, which looked like the way a pretentious Michelin-starred chef might slice cheese.

Another lady was looking after a broken curved screen, which first needs to be frozen in a super low temperature freezing oven to separate the glass from the display.

It speaks to how adaptable and intricate these technicians have to be. Just don’t ask them about foldable phones, they’re still working out just how to fix those notoriously fragile contraptions.

The fact that hundreds are processed at this factory alone each day, adding up to four million a year, reflects the great speed at which these technicians work.

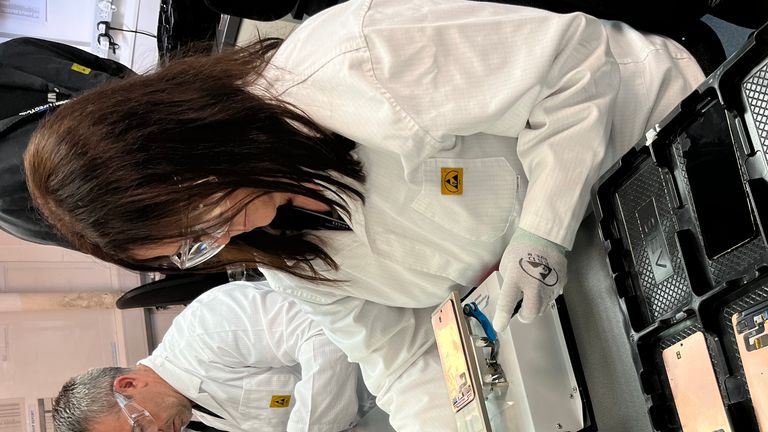

Not that they skimp on care and attention, hammered home by the fact even visitors like myself had to dress up in specialist protective gear that prevents me from passing any electrostatic discharge on to the devices – potentially ruining the repair process.

Read more:

50 moments in 50 years since first mobile phone call

They’re also helped by one of my favourite parts of the entire facility.

A web of pipes under the ceiling funnels replacement parts, packed inside cylindrical containers, to each work station as needed, like a hyperefficient Santa’s workshop.

I could have listened to the satisfying “woosh” as they take off for hours.

The ultimate factory reset

And the work doesn’t stop there, with data wiping also a key part of the job. After all, you definitely don’t want those WhatsApps and photos being seen by anyone else.

Coleman explains: “The technicians do the repair, but also the documentation.

“We’re approved by the major manufacturers, like Apple and Samsung, which gives us access to parts we need, but also the software tools to make 100% sure there’s no data on the device.”

A factory reset in the truest sense.

As was clear during my visit, this facility is always busy. But just as Santa’s workshop would perk up in December, it can expect plenty of old phones to play with come September when Apple unveils this year’s iPhone line-up.

Coleman confidently predicts his team will be handling traded-in iPhone 15s within weeks of release, such are some people’s obsession with always having the next best thing.

The idea of an annual upgrade is likely becoming increasingly alien to most of us, given how iterative and uninspiring new releases have long felt. Tim Cook is no doubt looking forward to telling us about “the fastest iPhone Apple has ever made”, but one imagines your old one will still cycle through funny TikTok videos just fine.

In fairness, manufacturers like Apple and Samsung clearly recognise how much longer we’re tending to keep hold of our phones, given both now let UK customers order their own self-repair kits if they feel confident enough to try.

Still, if you do fancy a new phone next month, it’s not for anyone to tell you it would be a waste of money.

Just remember you probably don’t have to let the old one go to waste.